It took me longer than I’d like to admit to finally choose a new series to write about. I purchased The After Life, Dark Engine, The Fade-Out, and The Woods before finally settling on Rick Remender and Greg Tocchini’s Low. Low is a sci-fi series that takes place after the decline of mankind (a world of regressing societies), and shortly before the destruction of the Earth as the death of the sun draws near. Remeder's story is enjoyable, but it was Tocchini’s artwork that initially pulled me in and then kept me reading. The artwork on the cover of issue one seemed more like something that should be framed and hanging on a wall to be admired rather than something I would thumb through and inevitably bend. As Douglas Wolk notes in his article Pictures, Words, and the Space Between Them, “every great” and most “decent-to-middling” artist “has a specific, intensely personal style,” (124), and although Tocchini's style is definitely distinctive, I am torn as to whether or not that can be attributed to his line work, or his colouring.

We are all taught that we are not supposed to judge a book by its cover, but when buying comics, the practice is necessary. The multi-modal nature of comic books means that much, if not most of the meaning we create when reading the text comes from the artwork. Wolk says that “the fact that drawing style is the most immediate aspect of comics means that what you see when you look at a comic book is a particular, personal vision of its artist’s vision,” (125). For myself, at least, this means that if we are to enjoy the work as a whole, it is important that we enjoy how that vision translates into images. Even before finishing the first issue, I was nearly determined to enjoy the story for the fact that I enjoyed the artwork so much.

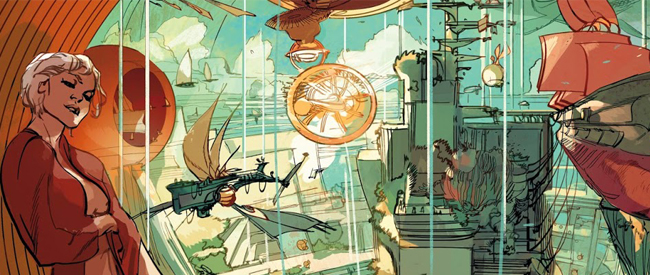

With my newfound love for Tocchini’s art style, it should come as no surprise that issue one seems more driven by what Jan Baetens calls monstration as opposed to the story's narration. Baeten describes monstration as “when the events are performed by the characters themselves in a situation in which the story seems to narrate itself, without any narrator’s intervention,” (149). The narrative is important for filling in gaps, but it is Tocchini’s artwork that sets about building a world that I want to explore.

|

| Image taken from www.brokenfrontier.com |

Tocchini’s

style is not one that relies on apparent divisions. His line work and colouring

do not always match up, but often bleed into one another. Oftentimes (nearly

every spread), panels overlap and cut off sections of one another, creating a

claustrophobic feeling that mimics the seemingly crowded cities and cramped

ships. When compared to this cramped layout, the sprawling panels (which often

stretch over two pages) depicting the ocean work to emphasis emptiness and

seclusion. Once again, it is arguably the artwork (monstration) throughout

these pages shaping the reader’s experience more than the narration.

As I’ve

briefly mentioned earlier, Tocchini is also responsible for colouring Low. His use of a

few dull colours lends to his unique, distinctive style, if not defines it

entirely. The cover, shown above (Figure 1), contains nearly all colours that

will be found throughout the issue. Depending on the location, single colours

tend to dominate entire spreads (blue/green when depicting the ocean, a golden

yellow when depicting the city, red when depicting danger, etc.), a theme that

continues in later issues as well, working similarly to braiding, in that

certain colours remind readers of certain locations in earlier pages and

issues.

As readers, Low presents us

with an interesting world, but more specifically, we are presented with beautiful

visuals which alone are enough to justify purchasing at least the first issue.

If you are interested in Tocchini’s other work, I recommend checking out his

blog (http://gregtocchini.blogspot.ca/), which contains earlier work, and work

in various stages of completion (which is particularly important when trying to

get an idea of just how much his colouring style gives life to his art).

Overall, Low has an interesting story that is sure to intrigue many

sci-fi fans, but it is the artwork that allows Low to stand out among

other series.

Works Cited

Baetens, Jan. “Revealing Traces: A New Theory

of Graphic Enunciation.” TheLanguage of Comics: Word and Image. Eds. Robin Varnum and Christina T.

Gibbons. Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 2002, 145-55.

Remender, Rick and Greg Tocchini. Low #1. Berkeley, CA: Image Comics, 2014.

Wolk, Douglas. “Pictures, Words, and the Space Between Them.” Reading

Comics. New York: Da Capo Press, 2007. 118-34

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)